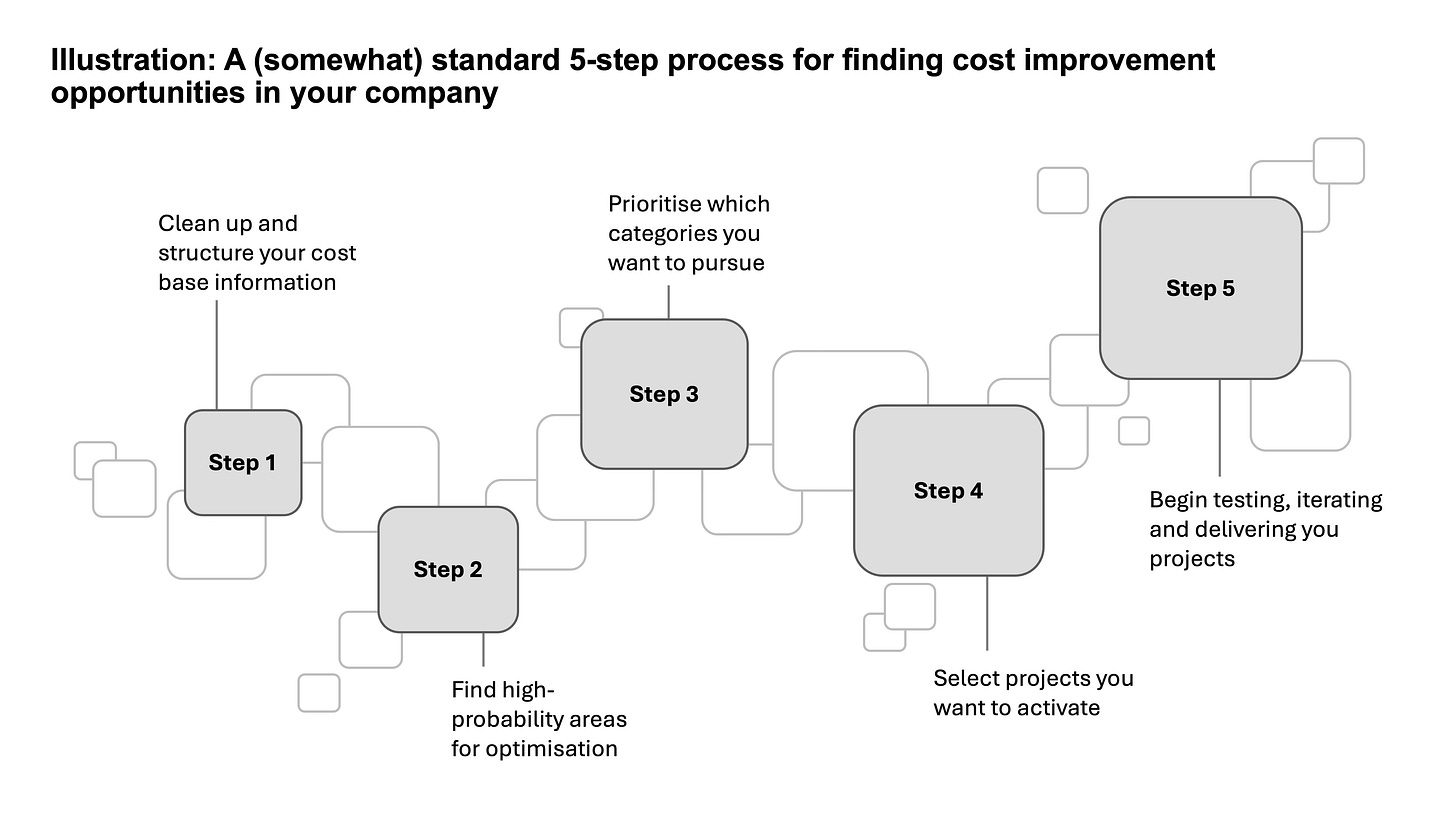

A (somewhat) standard 5-step process for finding cost improvement opportunities in your company

Where to find cost improvements and how best to look for them

Nearly every business has cost improvement opportunities. And usually, the bigger and more complex the cost base, the more (hidden) opportunities there are. The trick always seems to be in using a structured, systematic approach to identify and capture these opportunities. And to understand the trade-offs that are inevitably involved.

Note - the approach described below is just one way of going about finding cost improvements in your company. There are multiple variations and everyone seems to use whatever they find most intuitive and easy to follow. However, the major components seem to be the same no matter the situation.

Below is a visual representation of what the process looks like on a page:

Step 1: Clean up and structure your cost base information

It is very hard to find anything if your cost base information is a mess. We’ve seen numerous instances where all of the allocations (corporate to BUs, BUs to BUs, departments inside the BU, etc.) render your cost best nearly impossible to decipher. And of course, all of those cost allocations are not ‘real’ cost transactions. They are merely accounting tricks to try to represent the accounts more accurately. But in reality, they make things much more difficult to understand and analyse.

Secondly, a typical P&L is structured into standard categories - cost of good sold (or of services provided), marketing, selling & logistics, general & administrative expenses, other costs, and so on. However, this isn’t always the best format for looking for cost optimisation. There can be cases where the same expense (e.g., flights to site) can be allocated partially to cost of production, and partially to G&A. However, it’s the same type of cost, and the ways you can optimise it are similar.

The best way we’ve found how to structure your cost base is by ‘type’ of expense, rather than ‘function.’ Typical expense types include: (i) purchase of materials and consumables; (ii) purchase of services; (iii) labour and related expenses; (iv) capital projects-related costs. This is not the most neat or perfect way to structure the cost base, but it’s fairly practical. You can take this as a starting point and then adjust categories based on your situation.

Once you’ve done this ‘Level 1’ mapping of the cost base, you normally have to ‘double click’ into the biggest cost categories. The reason is that you want to know what exactly is hiding inside of them. This will come in very handy later on, when you brainstorm what are the ways you can optimise each sub-category.

Example ways how you can achieve this ‘Level 2’ mapping include: (i) by vendor or supplier; (ii) by type of material or consumable; (iii) by type of service provided; (iv) by department where employees work; (v) by part of the operation to which a particular cost relates (e.g., mine or processing plant). The more of the different data cuts you can make, the better. Later on, you can focus on the ones that give you the most useful information and park the other ones to the side.

Step 2: Find high-probability areas for optimisation

Often, when it comes to looking for cost optimisation opportunities, time is of the essence. There might be deadlines involved, imposed by powers that be. It might simply be inefficient to spend lots of lots of time looking for every incremental dollar you can save. There might be competing priorities around what else you could look to improve in your business.

The best way to get a good ‘bang-for-buck’ is normally to sit down and brainstorm which sub-categories you think have the highest probabilities of success in terms of lowering the costs. You might be able to tell this based on your own first-hand experience with the vendors or materials in specific categories. Or you might have heard from others around the place about certain categories having all kinds of inefficiency. Or you might discover that certain categories always get purchased in a rush, without following a rigorous cost-optimisation process upfront.

The more clues and guesses you have, the better it is, particularly if you have multiple clues point at the same cost categories. The only watch-out is that sometimes areas of high opportunity end up being quite small in the grand scheme of your cost base. If that is the case, you can still pursue cost improvements there. Just be mindful that the savings may be quite minimal.

Ideally, what you want to end up with after Step 2 is a list of cost categories that are both sizeable, but also carry high promise of finding cost reduction opportunities there. If that is not where you ended up, your cost reduction process might still be successful. It would just take longer to actually find and capture the reductions, as you would have to quite literally look underneath every rock to find them. It is much better to start with a strong list of ‘suspects’ to begin with.

Step 3: Prioritise which categories you want to pursue

Some cost categories might be easier to optimise than others. For example, certain services might lend themselves more readily towards cost reduction than critical process consumables. Not only can some services be scaled back, paused or in-housed altogether, but you can usually also look for lower-rate providers. You just need to be mindful of risks that might be involved.

Conversely, you can rarely reduce the volume (or quantity) of critical input materials that your business requires. There might be some inefficiency, of course, but chances are, if it’s a critical and expensive input, it usually gets analysed and paid attention to fairly closely. The only practical ways you can lower the cost on these consumables, then, is to try to find waste or over-use, or try to find alternative lower-cost suppliers.

Besides the ‘difficulty’ involved in successfully optimising a given cost category, you also need to try to estimate the ‘size of the potential prize’ involved. If it’s a smaller category, as mentioned before, you’d need quite a sizeable reduction to give you a good dollar-outcome in absolute terms. At the same time, a small relative reduction off a much higher spend base can give you quite a sizeable saving if you are successful.

Finally, there might be some ‘subjective’ considerations when you prioritise which cost categories to go after. As an example, sometimes your business has certain strategic partnerships, which you don’t want to disturb unless you absolutely have to. Or you might have already tried to renegotiate certain contracts not so long ago, so you might not have the appetite to open that same can of worms again. You need to factor things like that into your prioritisation exercise.

Once you’ve done your prioritisation exercise, the result can look something like a ‘heat-map’ chart, with different colours representing increasing priority of your target cost categories. You can then decide how best to place your efforts just by looking at the chart and seeing what it tells you. The goal is to try to give you a somewhat rigorous approach for selecting high-potential categories, rather than relying purely on opinions or gut feel.

Step 4: Select projects you want to activate

There are multiple types of activities and projects available for reducing costs in your business. Some of them might be ‘no-regret’ moves, like looking for obvious waste or over-use of production inputs. Others are less straightforward and might involve serious trade-offs.

Here’s an example set of activities and projects you might want to consider:

You can use the chart above as a checklist to see which ideas you have already explored. Even if you tried all of the ones on the list, you might find that some levers have been looked at in less detail than others. In a simplistic view of the world, if you did apply all of the ideas to their full extent, it would mean that there isn’t any further opportunity to reduce costs. You need to ask yourself if this is really true.

You might also decide that you aren’t going to pursue some of the levers. Reasons can include the fact that certain materials or equipment are too critical to risk getting wrong, for example. As a general rule, anything that relates to your overall bottleneck should be treated with absolute caution.

The end result of this step should be a list of ideas that you would like to apply in your cost reduction exercise. Sometimes pulling all of the levers can also be impossible to do given available human resources at your disposal. So you need to pick not only the right levers, but also the right portfolio of them, so your team can successfully deliver them within a reasonable timeframe.

Step 5: Begin testing, iterating and delivering your projects

It is not rare that you start with believing that certain types of costs can be reduced, but then find out a multitude of reasons why they can’t. This is normal. You need to bake in some margin that not everything you’re going to look at will result in improvements. So, in some ways, it is good to over-budget for what you’re looking for, so you can then ‘land among the stars’ (if you started off with ‘shooting for the moon').

Additionally, a lot of your cost reduction activities depend on factors external to your company. For example, what the market looks like for certain goods or services, how competitive it is currently, if there is over-capacity, if there are new entrants who might be more aggressive on pricing than long-established incumbents. It might be impossible to know what it really looks like until after you’ve tried to chase some cost improvements.

Therefore, the best strategy is to get going and start learning what you can about your cost categories of interest. It might also be the case that your existing teams might be too busy with their day-to-day tasks to do this effort properly. Even if they do it, they might do it half-heartedly, just to tick the boxes next time you ask them about their progress. You need to look reality in the eye and acknowledge if this is the case.

To address that, sometimes you do want to bring in temporary (or permanent) reinforcements to address this challenge. The alternative can always be doing things with your existing resources. However, it might take you 12 months instead of 3 to get the same results. And then you will have wasted 9 months of cost savings, which could have more than paid for the temporary surge in resources.

You can also be creative in your approach with team augmentation. For example, many good service providers might be open to a pay-for-results model. Under this approach, you might still pay them some nominal amount to cover their basic costs, but the rest of their compensation would be tied to actually delivering you the savings. It’s a win-win on multiple fronts, as it almost guarantees you a positive ROI, and also incentivises your contractors to deliver the results (vs get paid for their time no matter what actually happens).

Conclusion

Cost reduction is a task that many businesses eventually have to come to terms with. This is especially true for traditional, established businesses, particularly those in capital-intensive industries.

It can be true that sometimes the time is not right to focus on costs if you have bigger fish to fry. For example, as a mining company you might be in the middle of a price spike. In that case, you’re much better off maximising production temporarily, to make hay while the sun shines and recouping as much as your capital costs as you can. Even if your production methods might temporarily be not as cost-effective, it might still be a smart thing to do.

However, what normally follows periods of high prices are times of price declines. This is just the nature of commodity boom-bust cycles. And so the better prepared you are for those periods, the better your company is going to perform. And the more stable a place it will be for your employees, suppliers, shareholders and broader communities.